The highlight of my experience at the 2014 Tucson Festival of Books was two panels, both with Laurie Halse Anderson. The first was “Don’t Tell Me What NOT to Read: Teens and Censorship.” The second was “Edgy YA: Confronting Difficult Decisions.” Not surprisingly, the topic of censorship came up in the second panel as well.

Laurie Halse Anderson, in case you didn’t know, is the author of Speak, Wintergirls, and others. She’s tackled tough topics such as date rape, eating disorders, academic pressure, and (in her latest) PTSD.

Joining Laurie on the first panel was Chris Crutcher and Matt de la Peña. They’ve all written books that have been banned in various places and for various reason. On the second panel: Bill Konigsberg, Erin Lange, and Nicole McInnes. I hadn’t heard of any of these authors before, but some of them have books that sound interesting that I’d like to check out.

It’s no secret that our country has a long, inglorious history of banning books. Here’s just a taste of some classic books that are frequently on the hit list:

To Kill a Mockingbird

The Great Gatsby

1984

Animal Farm

As I Lay Dying

A Separate Peace

The Lord of the Rings

(To see more, go to the American Library Association’s list of Frequently Challenged Books.)

Why might books like these be banned? Well, I think Chris Crutcher summed it up nicely:

“When adults read something that makes them feel uneasy, they tend to think kids shouldn’t read it.”

I suspect these are the adults that want their kids to grow up thinking the world is nothing but puppy dogs and rainbows. There are people who want to believe that themselves, even though they’re adults and know better. Of course, people are free to think what they want and are free to decide what they do and do not want to be exposed to. I limit my news watching for that very reason. (Also, because mainstream news is irritating and leaves me feeling less informed, not more informed. But I digress.)

Laurie Halse Anderson has a different take on the reasons behind censorship. Given her vast experience in this area (almost every book of hers has been banned somewhere), she probably knows more about it than I do.

She said, “Censorship is a knee-jerk reaction to fear.” She said when talking to people about a book they want to ban, if we can “give them enough respect to understand what they’re afraid of, then there’s some possibility for growth.”

I respect her level-headedness about it. Chris Crutcher, who draws the inspiration for many of his stories from his years working as a counselor to children, wasn’t nearly so diplomatic and had no trouble saying so. I understand that, too.

Laurie noted that censorship can come from the right or the left. In her experience, books that contain topics about sexuality tend to get banned by individuals on the right, because they often don’t know how to talk to their kids about sexuality. Her book about eating disorders was banned by groups on the left, which she feels is because people on the left tend to not know how to talk to their kids about eating disorders.

I don’t know enough about it to know whether or not her assessment is accurate, but I thought it was an interesting point of view. And it was interesting to learn about books being banned by groups on the left, because you don’t usually hear about that.

All of the members of the panel on censorship expressed great admiration for the teachers, librarians, and school administrators who fight on behalf of banned books. Often, they’re putting their jobs (and therefore, their families) at risk.

Matt de la Peña spoke about visiting a school that wanted to ban his book Mexican White Boy. He ended up donating his honorarium in support of the cause, which drew him a round of applause from the audience. He talked about how it’s hard to get congratulated for what he does to defend his own banned books, when at the end of the day he goes back to his life while the teachers and librarians continue the fight, not knowing if doing so will cost them their jobs.

Along these lines, Laurie noted it’s important to let communities work things out for themselves, and only come and offer support if that’s what’s wanted. Sometimes people don’t want an outsider coming in and telling them what to do in their schools.

This entire panel really inspired me. Some of my favorite books are those that deal with heavy subjects, and are aimed at kids or young adults. (I talked more about that in my post leading up to the TFOB.) I appreciated books like this as a child, too.

I think books like this show respect to kids, because the truth is, they live in the real world just like we do. They have problems and challenges just like we do. Some of them have problems so severe it chills the blood. Books and stories have always been a way for people to better understand problems, emotions, and the human condition. Don’t our children deserve the opportunity to use stories in the same way?

When asked if banning is ever justified, Chris Crutcher gave a resounding, “No.” Then he said, “I can’t think of anything that isn’t better talked about than not talked about. These aren’t adult issues, they’re human issues, and they start when we’re kids.”

Laurie agreed. She said, “The worst thing you can do to any problem is not discuss it.”

Another great quote from Laurie: “We write resilience literature. We write books that give children strength.”

Laurie pointed out that when children read books about difficult subjects, that can be a great way to open discussion between children and parents. That’s a great opportunity to discuss with our kids our thoughts on all these things. She said, “Literature is how we pass on morality and guidance. We can’t withhold that from our children.”

Along those lines, in the second panel, Bill Konigsberg said, “Just because you read a book doesn’t mean you have to agree with it.” And of course, that’s true.

Maybe that’s where the fear comes in that Laurie was talking about. Maybe some people are afraid their children will read books and develop opinions that differ from that of their parents. Of course, kids will do that anyway, and that’s okay. We don’t need to control their thoughts and opinions. We really don’t.

I think literature is a great way to empower and educate readers of all ages. Sometimes it can give us a chance to understand other points of view, and thereby better understand ourselves.

Just as readers read to figure things out, writers do the same. Matt de la Peña said, “Writers write to figure out what they think about things.”

As I mentioned in an earlier post (which I linked above), one of my primary purposes for attending these panels was because I’d like to write these kinds of books in the future. I still have some fantasy books in the queue (and I do adore fantasy) but I have some more hard-hitting ideas germinating as well.

I’ll admit, I’m intimidated by my own story ideas. I came to these panels hoping for some guidance. I was not disappointed.

Matt said that when writing books for kids, there should be “no teaching. No preaching. No agenda. The job of the writer is not to diagnose the character, but just list the symptoms.” He also said not to approach it as an adult looking back. Be more immediate.

Chris said the pacing of YA literature may need to move a little faster, but really, a good story is just a good story.

When responding to a question about “categorizing” YA literature, Laurie said, “There are only two categories of books. Books that suck and books that don’t suck.”

Hilarious. I loved it.

I had the opportunity to ask a question, so I asked Laurie how she researches her subject matter so she’s able to give it the immediacy and genuineness necessary for someone going through it to feel like it really speaks to them.

She said to throw out any preconceived notions you might have. Ask a lot of questions and keep your mouth shut. In the end, we’re not that different as human beings. We operate from two poles, fear or joy. The rest is just details. Do the research.

I thought this was a great answer. It made me realize that, in terms of the writing process, these stories are no different from any other story. As writers we draw on our own experiences, we imagine what it would be like to be someone else or to be in a certain situation, and we give as much reality to that imagined story as we can.

I mean, after all, it’s not like I’ve ever cast a spell with a staff, but I don’t have any qualms about imagining what that’s like and writing it down anyway.

But, for me, the difference between writing about magic and writing about child abuse, is no one can say to me, “Oh no, I’m sorry, you got that completely wrong. THIS is what it’s actually like to cast a spell.”

I would hate to get things wrong about something like child abuse. But it’s more than that. I’ve learned the hard way that there are certain experiences you don’t really understand unless you’ve gone through it.

But. That’s what storytelling is for. Because stories can help us understand what something is like, even if we’ve never gone through it.

Erin Lange, from the second panel, said something I really needed to hear. She said, “You can still use your imagination and humanity to relate, even if you haven’t been through something that dark.”

Something about her saying this gave me permission to tell the stories I want to tell. Even if I’m not sure I’m ready to tell it.

Matt said, “Sometimes you have to take on a book that takes you out of your comfort zone. Take risks. If your reader feels too comfortable, you’re in trouble.”

I’ve learned enough to know that the fear of the blank page is always lurking around somewhere. Katherine Paterson, author of dozens of children’s books, many of them award-winning, said that with each new book she starts, she always gets to a point where she wonders if she knows how to write a book.

I read that interview with her years ago and I’ve never forgotten it.

Chris echoed this sentiment when he said, regarding the writing process, “It will always be scary.”

The reason why writers will always struggle with fear? Laurie put it well when she said, “No matter how many books you’ve written, you’ve never written this one.”

True that.

Why am I so drawn to difficult stories, particularly those aimed at our children? I suspect it has something to do with this…

In the second panel, Laurie was talking about the role these books play in our lives. Honestly, I don’t remember very well what lead up to this statement, but this is what struck me so soundly. She said, “All of us know that broken adult.”

I thought, “I am that broken adult.”

And I want to speak to the child I was then. I want to tell that story, and others like it.

So, it will be a while, but be on the lookout. At some point in the future, I’ll be bringing my readers a different kind of story than what they’ve seen from me before. I have no idea how that will be received. Regardless, at some point I will just have to take that leap into the dark.

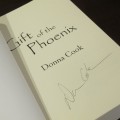

Pingback: Tucson Festival of Books Wrap Up | Donna Cook